Ten years ago, in the Caribbean Sea, a tropical storm formed, which would fundamentally change the way that millions of people in the US and around the world viewed climate change. That storm went on to become Hurricane Sandy, the strongest, most destructive, and deadliest Atlantic hurricane of 2012. Sandy killed more than 230 people across eight countries. In the US, the storm affected the entire Eastern seaboard, from Florida all the way to Maine. Its impacts were felt far to the northwest in both Michigan and Wisconsin. In the US alone, Sandy caused more than 60 billion dollars (USD) in damage.

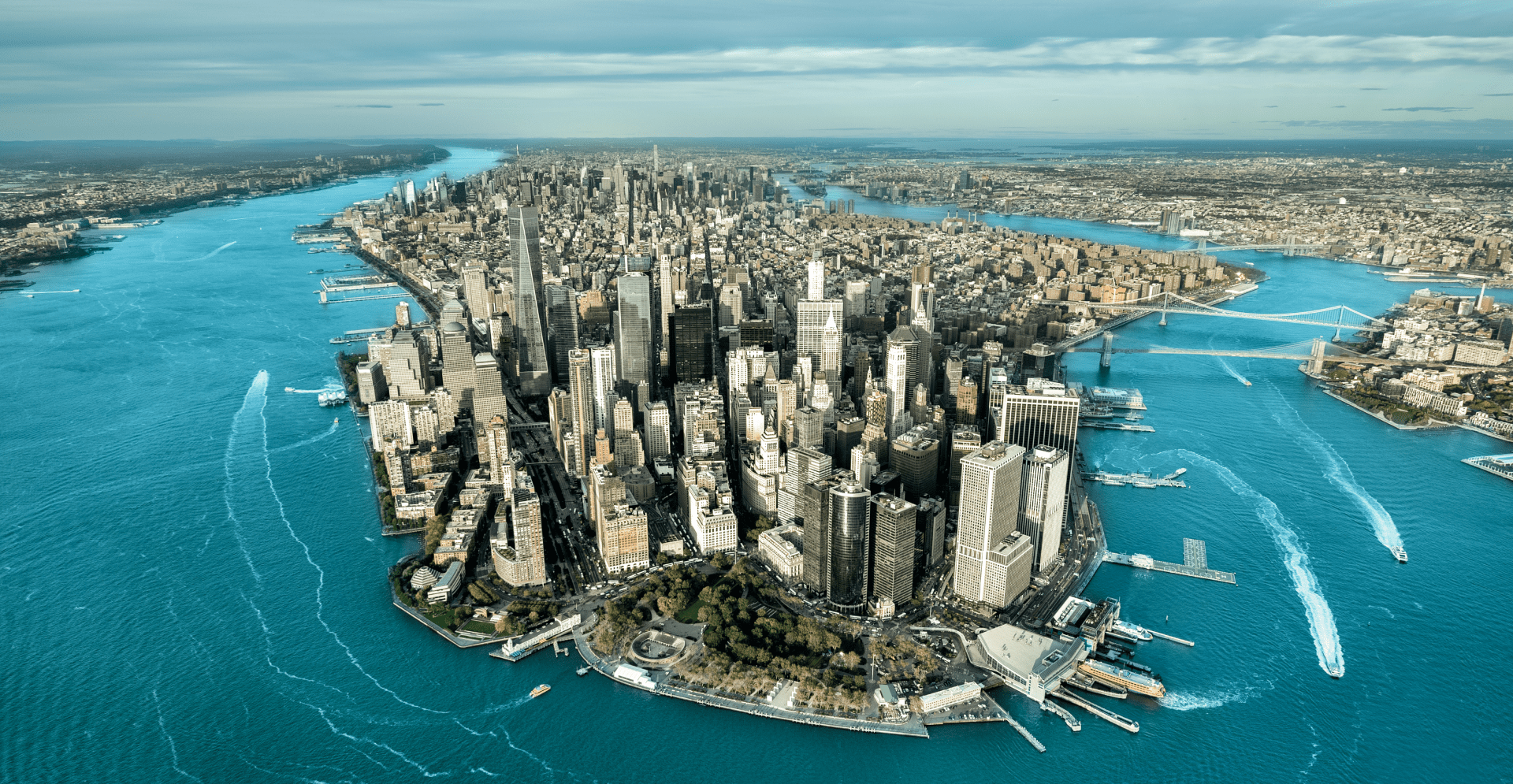

But without a doubt, Superstorm Sandy, as it came to be known, heralded the beginning of the end of the debate about climate change because of the devastation it caused in the world’s most prominent city: New York.

They say a picture is worth a thousand words. On 29 October 2012, the storm surge hit the Big Apple and over the ensuing days, thousands of pictures of a blacked-out New York City went out across the country and the world. Flood waters covered cars on the streets. Subway lines and tunnels were inundated. Hospital patients across the city needed to be evacuated because of the power outages. For tens of thousands of city residents and tens of millions of people around the world, in the short span of a few hours, the climate crisis went from an academic discussion point to reality.

It was clear we needed to do better

Before Sandy devastated America’s eastern seaboard there was real debate about whether the global climate was in fact changing, and if it was, whether human beings were the cause. Sandy made this question moot. No matter what you believed, we all could agree that we needed to do more to prevent the devastation and disruptions we saw in New York.

Before Superstorm Sandy, it was rare to hear city officials talking about coastal protection. In fact, this was frowned upon: often seen as flying in the face of how we’ve branded cities like New York – open, welcoming environments that are leaning into the future, without fear. Much of the climate discussion taking place in New York before Sandy was focused solely on mitigation, by making the city greener and more sustainable. And many people considered New York to have a low risk profile, when it came to coastal flooding, as most of the city is well above sea level (not withstanding the extensive underground infrastructure throughout the city).

But Sandy brought New York to a standstill. The casualties and direct damage to infrastructure were bad enough, but the knock-on impacts compounded the city’s problems. The storm surge devastated coastal areas like Breezy Point and flooded lower parts of the city. The flooding of the Verizon office, at 140 West Street, crippled Wall Street telecommunications and actually shut down the stock exchange for two days. A large part of the subway system was partly inoperable for several days, and it took much longer than that to get the system back to full capacity. And the flooding also destroyed water treatment facilities, creating an environmental disaster.

What we learned from Sandy and what we’ve done so far

In many respects, the main lesson we learned from Hurricane Sandy is a lesson humanity has to learn over and over again: we are not nearly as good at assessing risks as we think we are. We tend to underestimate not only how likely it is that events (like a massive hurricane hitting a massive city) can happen, sadly, we also underestimate the potential scale of the negative impacts if such an event does occur. As hard as we try, all too often we’re unable to fathom all of the risks at hand. Additionally, in preparing for the future we tend to be guided by what has happened in the past and this is leaves us ill-prepared for the unexpected.

Sandy brought the concept of resilience to the forefront of the urban planning agenda, not just for rebuilding New York City but for cities everywhere. In cities, in addition to protecting communities and businesses against the impacts of storm surges and sea level rise, resilience is all about making sure that critical infrastructure (like public transportation systems, hospitals, water, electricity, and emergency services) can operate come what may. We should all be able to agree that our cities should be robust enough to ensure that these services are available to residents no matter what.

And this led to quite a number of important projects that have the potential to make New York better prepared for the risks we can see from climate change but also for an uncertain future. For instance, Arcadis resilience experts have been supporting the City of New York administration in implementing projects following the conceptual action plan (known as the Big U) to protect Lower Manhattan. The East Side Coastal resilience project, which will protect 30,000 households and businesses in the Lower East Side, is under construction right now and we recently finished the masterplan, which aims to protect the Financial District and Seaport neighborhoods from storm surges, tidal waves, and severe rainfall.

That plan proposes the extension Lower Manhattan’s shoreline up to 500 feet or two full city blocks. This would also elevate the land to 20 feet or more above sea level. Also, to strengthen critical infrastructure, we helped Nassau County restore and protect their wastewater treatment facilities. We partnered with Verizon to harden their data facilities in New York so that future flooding wouldn’t disable Wall Street’s telecommunications. And we pitched in to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s effort to make the subway system more resilient.

What we’ve left undone

The Big U and many other resilience projects will undoubtedly provide better protection to some portions of the New York, but it’s important that we recognize that we haven’t done nearly enough to make the city truly resilient. These projects are not yet joined up into a comprehensive effort to safeguard the whole city. New York’s coastline is long and complex, and the sea level is rising. The coastline is 520 miles in length and includes inlets and rivers. When (not if) another major storm hits New York, certain parts of the city may fare better than they did during Sandy, but what about other parts of the city, which we have not yet bolstered?

We can feel proud about the significant efforts we’ve undertaken to make New York more resilient, but we also need to be clear-eyed about the fact that there’s so much more we still need to do. Currently, there are many impressive projects underway, which we need to now link together. We also need to recognize that climate change isn’t just about storms and flooding. Around the world, nearly all of our cities are highly susceptible not only to floods but also to drought, water shortages, heat stress, ecosystems impacts, and wildfires. We must also focus our efforts on making urban environments more robust in the face of these challenges, so that our cities remain functional and livable no matter what the future holds.

As we commemorate the 10-year anniversary of Superstorm Sandy, the real questions we need to ask ourselves are how can we stop climate change by reducing our carbon footprint, and at the same time rapidly ramp up our efforts to make New York more resilient. But more importantly, we must figure out how to replicate the successes we’re achieving in the Big Apple in cities everywhere.